When the Shutter Refused to Look Away

- Llerraj Esuod

- 11 minutes ago

- 3 min read

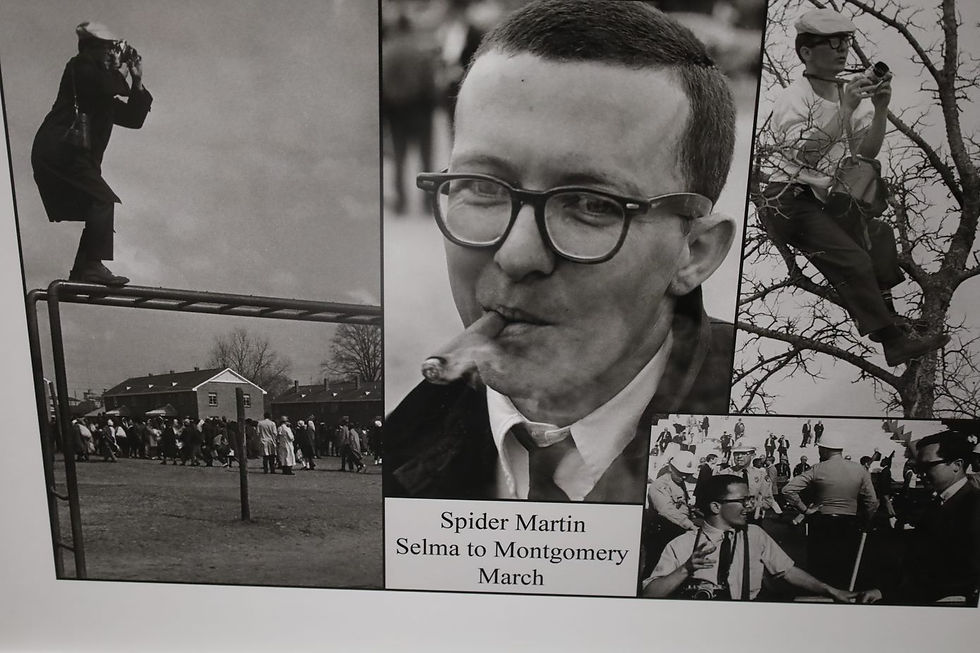

Photo Credit: The NYTimes

By Llerraj Esuod

Photojournalist James “Spider” Martin stood on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, aperture tight and depth of field unforgiving. He adjusted exposure as his camera’s flash cut through police lights and Alabama state troopers advanced, capturing violence in real time.

The year was 1965.

History, Caught in Spider’s Web

“I got those pictures because I was there. I never left,” Martin later said. “I stayed because they wanted me to leave, and that angered me. I knew what was happening.”

Bloody Sunday

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were tested before a national audience on what became known as Bloody Sunday. More than half a century later, those time-stamped frames—once rushed into print and powerful enough to shift public opinion and prompt federal action—return with restored clarity through a 21st-century lens in Selma Is Now: The Photography of Spider Martin, opening Jan. 31 at the African American Research Library and Cultural Center.

Time Didn’t Soften

Drawn from the Spider Martin Photographic Archive at the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas, the restored collection documents the Selma marches not as distant artifacts but as lived confrontations. Time has not softened them. If anything, restoration sharpens their edge.

A Nation Moved

“Spider, more than any other photographer, used his camera to advance the struggle for civil rights in Alabama,” civil rights icon John Lewis once said. His images, Lewis added, did not transform only the American South but the nation itself.

Democracy Exposed

The work operates as a series of cultural conversation pieces. It illustrates Selma’s role in galvanizing the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, reinforcing a civic responsibility to protect the fragile architecture of the republic.

Faces at Risk

Within the four corners of each frame are expressions both fearful and fearless—ordinary citizens braced to absorb the risk of imminent repression delivered with the mechanized precision of state force. These scenes capture Black resistance against white brutality and continue to reverberate in contemporary debates over representation, voter access, and justice.

History Speaks

“Selma Is Now asks us to face the courage and the cost of fighting for democracy,” said Dr. Tameka Bradley Hobbs, historian and library regional manager of the African American Research Library and Cultural Center. “These images remind us that ordinary people, united by conviction and community, can change the course of a nation.”

No Clean Ending

Central to the presentation’s relevance today is its insistence on collective agency. The archive resists closure. It does not allow Selma to be neatly sealed off as a resolved chapter in American history. Instead, the photographs encapsulate the nation’s conscience, offering a prism through which the present is examined and unresolved questions of power, participation, and belonging come into focus.

The Work Isn’t Finished

Doug McCraw, founder of FATVillage, describes the effort as “deeply personal.” Raised in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, McCraw said revisiting Selma’s history forced him to confront how much of that struggle remains unfulfilled.

“My decision to produce this presentation is firmly rooted in my upbringing,” McCraw said. “As I revisited this history, I was struck by how many of the same challenges endure today. The fight for voting rights, equality, and the freedoms promised by the Constitution remains unresolved.”

A Present Tense

Chevara Orrin, an equity strategist and daughter of civil rights leader James Bevel, believes the images demand more than reflection.

“These are not just historical records. They are a mirror, a portal, and a call to conscience,” Orrin said. “They demand that we confront the raw truths of injustice and remember that the pursuit of equity is not a closed chapter. It is an urgent present.”

More Than Memory

Taken together, the body of work conveys urgency while resisting nostalgia, positioning the 1965 marches as a living inheritance—one that requires active stewardship and vigilance—echoing Lewis’s belief that these photographs helped bend the nation toward justice.

The Question

The images impose responsibility. They ask viewers to see themselves in the faces on the Pettus Bridge and to recognize democracy not as an abstract promise but as a brittle, human task—one that demands courage across generations.

The shutter did not look away then.

The question left behind is whether we will now.

“Mississippi Goddam”

Written in 1964, the song captured the moral insistence and anger of the civil rights era, indicting racial violence across the South—not just a single state.

Comments